Baltimore enjoyed a long tradition of flag making during the nineteenth century. Women always played a major role in the assembly and production of flags and banners. The most well known of this largely unrecognized group is Mary Young Pickersgill. She was responsible for the massive US flag that waved over Fort McHenry during the 1814 Battle of Baltimore. Pickersgill, ably assisted by daughter Mary, her nieces, and Grace Wisher, an African American indentured worker, produced the 30’x 42’ flag which so stirred Francis Scott Key to put his pen to paper to write the poem that later become our national anthem.

Dressmaking suppliers, more commonly known as “trimming stores,” engaged in the first large-scale production of flags starting in the 1840s. A handful of businesses competed in either the sale or the manufacturing and sale of “thread, tapes, lacets (braided tape in lace), galloons (decorative woven trim), bindings, buttons, corset rings, spool cotton, hooks and eyes [and] ribbons.” Some suppliers also carried hosiery, gloves, various types of yarns and clothing patterns. However, the making of “regalia,” decorations or insignia indicative of an office or membership in an organization, could also be quite lucrative. The numerous city-based independent militia units, fraternal associations, and church organizations all required specialized fabric items such as uniform trimmings or banners.

The entrepreneurial Charles Sisco (1811-1846), born of German immigrant parents, stands as a pioneer in the manufacturing of trimmings, regalia and flags. The Baltimore-based firm which bore his name arose in 1835 when Sisco transitioned from coach making to producing and selling fancy dress trimmings. He and his spouse Julia Ann Harper Sisco (1817-1888), who went by the name Ann, first set up a modest workshop within their own home. After an 1840 visit by the Baltimore Sun, the newspaper reported glowingly on Sisco’s success and his specialized manufacturing equipment, almost all of which he had supposedly invented. In contrast, his competitors imported much of what they sold. Sisco’s workshop employed men, women, and some youths, though the exact manufacturing roles they each played are unknown. Reflecting upon the scenes, the journalists concluded that “[t]he two things uppermost in our mind on leaving the establishment were, a sense of our independence on foreign manufacturers, and a feeling of pleasure, at seeing so many women profitably employed, in an occupation so suitable to their sex.”[1]

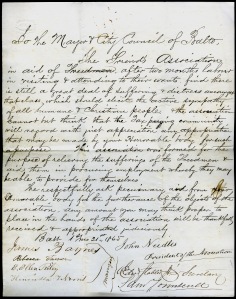

Upon Charles Sisco’s untimely 1846 death, 29 year old Ann assumed the management of the business, quickly renaming it “A. Sisco.” She led the firm for fifteen years, along with the ongoing responsibilities of several young children and a new spouse. (He did not work alongside her in the business.) Her company soon faced increased competition from local firms, some who set up showrooms but a few steps away from hers. As a result, she sought new markets elsewhere. In 1849, Sisco began advertising in a North Carolina newspaper announcing “Mrs. Ann Sisco… Manufacturer of Odd Fellows, Masonic, and Sons of Temperance Regalia… Also Flags and Banners constantly on hand and made to order in every variety of style” and employed a local agent to source new business from the southern states. [2]

During the 1850s, the firm of Gibbs and Smith became Ann Sisco’s main business rival. Edward Gibbs and Henry Smith, both former Sisco employees, brought with them the essential knowledge and skills necessary to run a trimmings and flag making manufactory. Gibbs' own leadership role in the Maryland Odd Fellows, a fraternal organization, no doubt helped him to source contracts in the direction of his firm. Several newspaper accounts remarked on the high quality of silk presentation flags produced and delivered by the company for organizations in Baltimore, Washington, DC and some southern states.

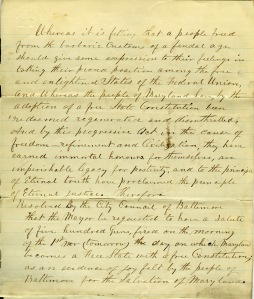

By 1860, with the storm clouds of an impending civil war gathering, both Sisco and Gibbs competed head-to-head in the flag making business. Each firm viewed the patriotic fervor of that time pragmatically and sought to maximize the money-making potential of the historic moment. In November 1860, both businesses contracted to make “secession flags” (based on South Carolina’s “palmetto” state flag) for Baltimoreans who favored the Southern cause. However, Gibbs and Sisco went even further. They started producing fabric cockades, a ribbon rosette, in colors that signaled the wearer’s allegiance. Red and white ones, the colors of the Confederacy, soon appeared throughout the city on the lapels and dresses of secession sympathizers during the winter of 1860-1861. [4]

The bombardment and capture of Fort Sumter initiated America’s Civil War in April 1861. This attack inaugurated what flag historian Marc Leepson labeled “flagmania” in the North and the demand for US flags grew exponentially. As Union regiments formed hastily, they all required a national flag to lead them forward to southern battlefields. Further, private individuals desired flags for display outside of their home or office. This same “mania” also took hold in the Southern mind with a similar fervor for the newly adopted flag of the Confederacy.

The beginning of war, however, also witnessed the departure of Ann Sisco from the leadership of her company. For unknown reasons, she stepped away from the day-to-day business operations and placed the responsibilities on her two sons, Charles and John Sisco, both men now in their early twenties. She subsequently sold the business to them. Sisco Brothers continued in operation until the early twentieth century.