In 1866, Der Deutscher Union Verein von Maryland (The German Union Club of Maryland) erected Baltimore’s first Civil War monument.[1][2] It celebrated the memory of Maryland’s Unionist Governor Thomas Holliday Hicks (1798-1865), who many thought helped to prevent Maryland from seceding. The monument’s organizers were drawn largely from the ranks of the Unconditional Unionist party, individuals who had promoted the immediate emancipation of the enslaved.[3] Why erect a monument to Governor Hicks? The dedication plaque underscored the reasons:

As a tribute to a native born citizen it is an object lesson to posterity of the gratitude, patriotism and unswerving loyalty of the German-Americans of Baltimore in the War for the Union.[4]

The Union Verein solicited funds and commissioned the monument. The club chose Haino [Heinrich] Isermann (1826-1899), a naturalized US citizen born in Germany, to be the monument’s sculptor. Unfortunately, no image of the 1866 Hicks monument has been discovered to date. We know with certainty, however, that the statue was a portrait bust set upon a tall and heavy pedestal. No exact information as to its size or dimensions has been found but existing documents suggest that the sculpture was made of marble and larger than life, or was in what is known as “heroic” size. Its pedestal featured a bronze dedication plaque.

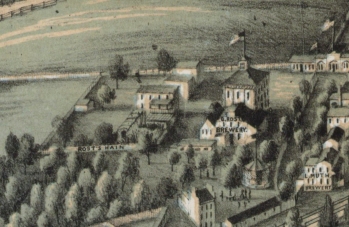

The Union Verein first offered the completed work to the City of Baltimore. However, the City supposedly denied the sculpture a place in any of the squares or parks.[5] It appears that the Union Verein had no alternative but to locate the monument on private land. “Rost’s Garden,” a pleasure park connected to George Rost’s (1817-1871) brewery, served as the monument’s first site. The Garden as the setting for the monument made sense for numerous reasons. Rost, another naturalized citizen from Germany, had stood staunchly with the Union, even heading a local soldiers’ aid society.

The Union Verein first offered the completed work to the City of Baltimore. However, the City supposedly denied the sculpture a place in any of the squares or parks.[5] It appears that the Union Verein had no alternative but to locate the monument on private land. “Rost’s Garden,” a pleasure park connected to George Rost’s (1817-1871) brewery, served as the monument’s first site. The Garden as the setting for the monument made sense for numerous reasons. Rost, another naturalized citizen from Germany, had stood staunchly with the Union, even heading a local soldiers’ aid society.

The formal dedication of the Hicks monument occurred on Thursday, June 7, 1866. Union war heroes General Franz Sigel, Union Army group commander, and Colonel Faehtz of the Eighth Maryland Regiment, among others, made celebratory speeches. The ceremonies concluded with a jovial feast and plenty of “gertensaft” (amber beer), all provided by “patriotic Old [Mr.] Rost.”[6]

Rost’s death, a change of ownership of the Garden, and the growth of Baltimore itself would ultimately affect the monument’s surroundings. However, until the mid-1890s, Irish fraternal groups, Bohemian gymnastics contests, church groups, political clubs, and gatherings of Civil War Union veterans, all continued to gather under the stony gaze of Governor Hicks.[7]

Baltimore City’s growth and the redevelopment of the land ultimately necessitated the removal of the Hicks monument in 1896. The Baltimore City government, under Republican Mayor Alcaeus Hooper, promptly came forward with assistance. The City Council passed a resolution to fund the dismantling, removal and storage of the statue. It also directed the Baltimore City Art Commission to select “a suitable site in a public square or park” for the monument’s permanent home.[8] The monument was removed from its setting, transported, and placed within an outdoor marble yard in West Baltimore.

An advocate for the monument’s re-erection soon materialized. Union veteran J. Leonard Hoffman (1843-1920?), an energetic naturalized German-American citizen, as part of a committee, spearheaded the task of finding a permanent home for the monument. Hoffman approached the Art Commission regarding the preservation and display of the monument. A Commission sub-committee advised Hoffman against pressing for the monument to be placed on public land.[9] The monument, due to years of exposure to the outdoor weather, needed a thorough cleaning and the dedication plaque also had warped with age.[10] Hoffman’s committee successfully lobbied for State funding for the monument’s restoration. [11]

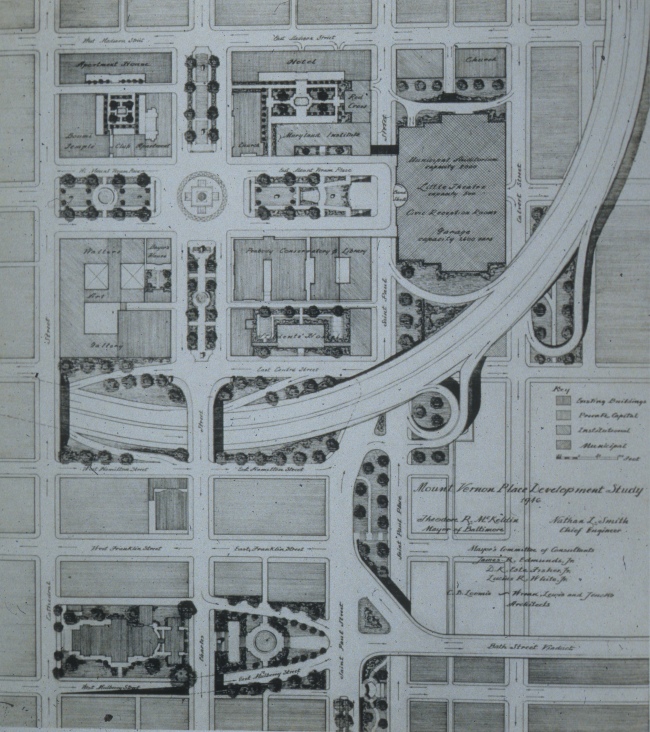

Finding a permanent home for the monument came next. Hoffman, on the advice of the Art Commission, first made an overture to the Maryland Historical Society. The Society appears to have considered accepting the monument as “a work of art” and not an historical object, but in the end rejected the offer.[12] Ultimately, it was the Maryland Institute (known today as the Maryland Institute, College of Art or MICA) that agreed to serve as the final location for the monument. It selected a most prominent and visible location for the monument within its then harbor area building: “Against the wall at the head of the stairs leading up from the main entrance”.[13] On August 19, 1898, the Hicks monument, at long last, was re-erected.

Unfortunately, the monument’s new home proved to be a rather short-lived sanctuary. In the early hours of Sunday, February 7, 1904, a smoldering fire ignited within a building located many blocks west of the Institute. The emerging flames were soon wind-swept eastward and gave rise to a two-day conflagration known as the “Great Baltimore Fire”, which consumed some seventy blocks of the central business district, including the Maryland Institute. The Institute’s roof and walls collapsed unto itself, destroying all that was within. Only the monument’s bronze dedication plaque survived the inferno. Yet, even that has now been lost to time.[14]

NOTE: This post is derived from the full-length article on the Hicks Monument entitled “Baltimore’s First Civil War Monument: An Object Lesson to Prosperity on the Loyalty of the German-Americans” by Robert W. Schoeberlein appearing in The Record [The Journal of the Society of the History of Germans in Maryland], V. XLVIII, March 2020, p.12-25.

[1] See the “Maryland Military Monuments Inventory” compiled by the Maryland Historical Trust for the dates of all monuments: https://mht.maryland.gov/documents/PDF/monuments/MMM-Inventory.pdf

The Gleeson monument, to a deceased Confederate soldier, was designed to be situated within a cemetery. The Hicks Monument, however, was always intended to be placed in a public space.

[2] Der Wecker, June 6 and 7, 1866.

[3] Henry Elliott Shepherd, History of Baltimore, Maryland, from Its Founding as a Town to the Current Year, 1729-1898… Etc, (Uniontown, PA.?: S.B. Nelson, 1898). 165. Unconditional Unionist 1866 meeting leadership rolls included Christian Bartell, Franz Sigel, E.F.M. Faehtz (these three individuals spoke at the monument dedication ceremony), William Schnauffer and Anton Wieskettle. Identified members of the Union Verein included George Rost, H.F. Wellinghoff, Karl Seitz, William Eckhard, and W.F. Bissing.

[4] Sun, June 18, 1905.

[5] Sun, April 21, 1897.

[6] Der Wecker, June 8, 1866.

[7] Sun, June 22, 1891.

[8] First Branch Journal, May 11, 1896, 822.

[9] Sun, April 21, 1897.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Laws of the State of Maryland… April 1898, (Baltimore: King Brothers, State Printers, 1898), Chapter 440, 1053-55.

[12] Sun, April 21, 1897.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Sun, June 18, 1905.