In mid-June of 1863, great alarm gripped Baltimore. The Confederate Army under the able command of General Robert E. Lee had crossed into Maryland and might advance in an attempt to take the city. Meetings to organize citizen militias took place throughout the wards. White male citizens, members of the various Union League chapters and the Union Club, mustered into home defense units. If Baltimore fell, the surrender of Washington might be inevitable.

On Saturday, the 20th of June, Mayor Chapman called a special session of City Council to consider the erection of additional defensive fortifications around the city. In all, “twenty-two works of defen[s]e, of various size and strength… which, in case of attack… would be very difficult to break” were envisioned. Supported in the endeavor by General Robert Schenck, the regional military administrator, with his offer of supplies and tools to assist in the task, the Council approved $100,000 to build earthen bulwarks to secure the city from Rebel attackers. The U.S. Army ultimately decided on the final location and the types of fortifications to be built.

Baltimore agreed to supply the manpower. General Schenck, however, required the immediate service of 1,000 men by 4PM on the very same day. Could such laborers materialize seemingly from the air? Schenck offered some additional assistance in the form of martial persuasion: “If you have any difficulty in furnishing the labor… I will furnish you the military power to enforce… impressment.”[1] Impressment meant that any person could be seized, without notice, and forced to work, on the fortifications.

The Baltimore City Police, supported by the military, immediately set about gathering all able-bodied men. They, however, singled out only African American males. The hapless men were simply arrested and forcibly marched out to the outskirts of the city under armed guard. It is doubtful that the men had any opportunity to even leave word with family or friends about their fate. A few apparently resisted though not without consequence. An African American “servant,” a local euphemism for the word “slave,” of one Mrs. Fenby was shot in the foot as he tried to escape from his impressment.[2]

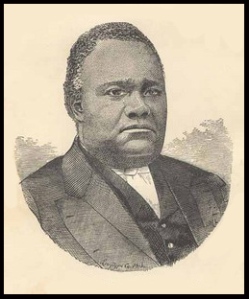

The heavy-handed actions of the authorities were unwarranted and an insult to the patriotism of the men. Reverend Alexander Wayman (1821-1895), Pastor of the Bethel A.M.E.Church and a leader in the African-American community, inquired about his son at a local police station and narrowly escaped being sent to work. Before leaving the station, he voiced, “Gentlemen, there is no need of the police officers running after us… this way. All that was necessary was to let us know that we were wanted, and you could have five thousand of us before sun-down.”[3]

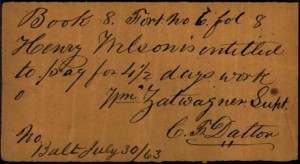

Work on the fortifications took place around the clock. Wayman went out again to visit the workmen on early Sunday before his church service, and, once more, was almost made to shoulder a spade. Wayman advised the workman to “be brave” and assured them that “it will come out all right.”[4] The City did eventually come around as Wayman predicted. The City Fathers decided to pay each worker one dollar per day plus rations. Yet, it was a hard-earned dollar, an especially tough, back-breaking labor made worse by the clay-like soil that characterizes most of the region. The fortifications put up varied in size but they all required the same mounding up and compression of soil. Armed with only pick, shovel and spade, and a large measure of determination on the part of the men, the earthworks did rise.

Heavy labor and hot sun made the work tough but overt racism while on their marches to and from their worksite made things even more onerous. Some white men and boys hurled stones or else insulted them along the way. The African American workmen devised the means to end these incidents. They took up a collection from among themselves and purchased a US flag which would, henceforth, lead them forward on their marches. From that moment forward, any attack upon them was seen as an attack upon the flag so that the city police, prompted by the Provost-Marshall, provided them with additional protection. In an ironic turn of events, three white men who interfered with the workmen “were taken before the military authorities, who ordered them to labor four weeks on the fortifications with the negroes, without pay and [at] half-rations.[5]

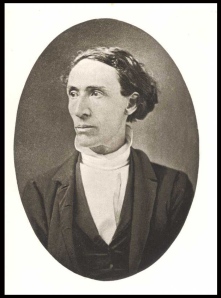

Not all whites, however, held a low opinion of the men. Many appreciated what they were doing to benefit all Baltimoreans. The mere sight and sound of the marching men greatly impressed one resident of Madison Street, a major east-west artery. The Reverend William Whittingham (1805-1879), Protestant Episcopal Bishop and a staunch Union sympathizer, viewed many columns of men passing by his home on the morning of July 4th, a day typically set aside for rest and celebration. These times, however, were very different and the Confederate Army, though bloodied from the Gettysburg battlefield, would soon be on the march again. Bishop Whittingham recounted:

Daily, now, morning and evening we have long processions of hundreds (sometimes, as [in] last night, thousands) of blacks returning from work on the outer fortifications. They work by relays, night and day, and are working all day today, holiday or not. They march two by two or four by four, with flags, sometimes singing – with much pride in their employment and evident content[ment] – altho’ they tell funny stories about the way in which they in which some… were run down and forced into service.[6]

To be continued…

[1] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: Series 1, Vol. XXVII, Part III (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1889), p. 235.

No comments:

Post a Comment