[On the 20th of June, 1863, hundreds of Baltimore’s African American men were pressed into service to build earthen fortifications to further secure the city from a Confederate Army attack. It was very hard labor for a wage of $1 per day plus rations. ]

General Robert C. Schenck, the regional military commander stationed in Baltimore, took notice of the men and their work. He “repeatedly urged President Lincoln to authorize enlistment of the several thousand blacks, mostly free, who labored on the fortifications around Baltimore”[2] and “to create from among them a reg[imen]t of Sappers & Miners.”[3] The President eventually agreed to Schenck’s request and Secretary of War Stanton appointed Colonel William Birney, the son of antislavery politician James G. Birney, to take charge of recruiting the workmen. Birney established a Baltimore-based recruiting office in Mid-July and in less than seven weeks filled the ranks of the Fourth US Colored Troops.

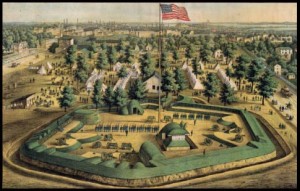

On the 20th of July, hundreds of African American laborers from the various project gathered together for a special ceremony. They assembled at Fort No. 1, also known as Fort Davis, on West Baltimore Street (in the area of today’s Bon Secours Hospital) for the purpose of a flag presentation. The laborers had pooled together their money to purchase a very large, garrison-style flag for the use of the soldiers stationed at the fort.

Some special guests were also present. Two companies, about 160 men, of the newly formed Fourth United States Colored Troops, stood at attention, the gold buttons of their new blue uniforms glinting in the waning afternoon sun. It would be sometime in late August before they would be issued any firearms. These soldiers, likely constituting Companies “A” and “B,” had been in army dress for only five days.

The workmen chose Colonel Birney to make the presentation speech on their behalf. Here is an excerpt:

The flag they present you to-day, is in token of their loyalty. Their hearts are true. Whoever else may be swayed from duty, the black remains firm. Pluck him from the very core of rebeldom and he is a true man. You may trust him. All his aspirations are for the success of the right, the triumph of the nation. For him the success of traitors is his own degradation, the dishonor of his family, the doom of his race to perpetual infamy.

You may regard, sir, the presentation of this fine flag, as implying the readiness of the men of color to defend it. You have witnessed their alacrity in springing to the lines of these fortifications when Baltimore was menaced, their cheerfulness in volunteering their labor, their patience in its prosecution. These forts around the city will be monuments of their patriotism. [emphasis added] With equal alacrity, sir, do they respond to the call of the country, “To arms!” When the Goddess of American Liberty hands them the musket, they accept it with stalwart and ready arms, thankful to Providence that their frugal diet has prepared them for the soldier’s rations, that their life of continuous labor in the open air has inured them in advance to the hardships of campaigning, and that they have not now to learn patience and obedience, these two virtues of the soldier.[4]

Some of the workmen did step forward to join the ranks of their brothers and shoulder a musket for the Union cause. In the ensuing months some 1,000 African American men, from Baltimore and elsewhere in Maryland, would fill the ranks of Colonel Birney’s command.

By the end of August, most of the work on the fortifications had been completed.[5] The forts served their purpose but were never actually tested in battle. The closest Confederate incursion came in July 1864 when Major Harry W. Gilmor with 135 men from the First and Second Maryland Cavalry (CSA) regiments traveled down the York Road as far as Govanstown (Govans), then a part of Baltimore County.

With the Civil War’s end, the fortification sites themselves became immediately obsolete and a hindrance to future city development. Rather than the forts being “monuments” to the patriotism of African American men, the work soon commenced to obliterate them in their entirety. All buildings were first auctioned off as surplus US Government property. Next, though it took several years, the city passed ordinances calling for the dismantling of certain earthworks. Fort No. 8, just south of Greenmount Cemetery, was leveled in 1869 while the Fort Federal Hill breastworks remained until 1879. But unlike the vast majority of the forts, both locations would eventually be designated as public parks, Johnston Square and Federal Hill, respectively. Most became the building sites for Baltimore’s famed row houses. Fort No. 1 finally succumbed to development in the 1890s.[6]

[1]A Union soldier was entitled to receive daily 12 oz of pork or bacon or 1 lb. 4 oz of fresh or salt beef; 1 lb. 6 oz of soft bread or flour, 1 lb. of hard bread, or 1 lb. 4 oz of cornmeal. The marching ration consisted of 1 lb. of hard bread, 3/4 lb. of salt pork or 1 1/4 lb. of fresh meat, plus the sugar, coffee, and salt.

[2] The Black Military Experience , Ira Berlin, editor ; Joseph P. Reidy, associate editor, Leslie S. Rowland, associate editor. (New York : Cambridge University Press, 1982), p. 184.

[3] Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 6. (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), p. 317.

[4] Christian Recorder, July 26, 1863.

[5] Sun, August 28, 1863.

[6] Sun, November 24, 1903.

![Payroll Slip, [July 1863] BRG41-3-1497A](https://baltimorecityarchives.files.wordpress.com/2013/07/untitled-1.jpg?w=300&h=182)

No comments:

Post a Comment