The Hospital at Baltimore

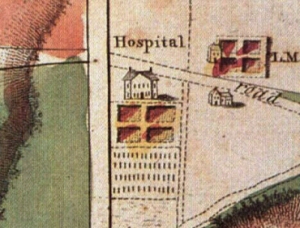

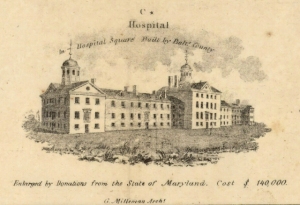

The circumstances surrounding the founding of the Hospital in Baltimore, the first medical institution in Maryland to specialize in the treatment of mental illness, remain obscure. The waves of yellow fever that visited Baltimore during the 1790s saw the hasty construction of temporary buildings and a tent city for residents upon the high ground above Fell’s Point. This site, chosen for its supposed better air and good drainage, would eventually serve as the six and three-quarter acre grounds of a permanent hospital. The Warner and Hanna map of 1801 (see above) is the first to depict the existence of the hospital, showing a main building, complete with a formal garden and walkways. Though this is likely a fanciful depiction, the remote location, some one-half mile from any densely settled area, likely ensured a peaceful setting for the convalescent. Oriented to the south on a hill, the hospital overlooked the distant Baltimore harbor. One discordant feature, however, was the presence of a graveyard or Potter’s field directly opposite the hospital’s front facade. Commenting upon the sight of the graves, a later visitor to the institution remarked, “I think [it] rather depressing to the spirits of the unfortunate invalids.”

The circumstances surrounding the founding of the Hospital in Baltimore, the first medical institution in Maryland to specialize in the treatment of mental illness, remain obscure. The waves of yellow fever that visited Baltimore during the 1790s saw the hasty construction of temporary buildings and a tent city for residents upon the high ground above Fell’s Point. This site, chosen for its supposed better air and good drainage, would eventually serve as the six and three-quarter acre grounds of a permanent hospital. The Warner and Hanna map of 1801 (see above) is the first to depict the existence of the hospital, showing a main building, complete with a formal garden and walkways. Though this is likely a fanciful depiction, the remote location, some one-half mile from any densely settled area, likely ensured a peaceful setting for the convalescent. Oriented to the south on a hill, the hospital overlooked the distant Baltimore harbor. One discordant feature, however, was the presence of a graveyard or Potter’s field directly opposite the hospital’s front facade. Commenting upon the sight of the graves, a later visitor to the institution remarked, “I think [it] rather depressing to the spirits of the unfortunate invalids.”

Knowledge of the facility’s interior comes mostly in the form of visitor accounts and reports of the yearly inspections by the hospital board. In the 1820s, one could tour the facility for the sum of 12 ½ cents. The mentally ill, however, were not intentionally exhibited, as had been the case at the Pennsylvania Hospital. Anne Royall, the published travel diarist, toured the Baltimore facility in 1824. After viewing the wing dedicated for the mentally ill, she wrote:

It is against the rules of the institution to suffer strangers to see the insane; this prohibition proceeds from motives of delicacy towards the friends and relations of those afflicted, who do not wish them exposed. The doors of their cells are secured with bars of iron and heated by furnaces placed on the outside of the wall, one to every room, which conveys heat to the patient. I looked into some of these cells, which were vacant; they were similar to those occupied by the sick, excepting the bedsteads, which were of iron, and without chairs or tables. Though I could not see the unfortunate beings, I could hear them utter the most shocking oaths.

The noises Mrs. Royall heard likely emanated from the patient cells within the basement. The mentally ill deemed violent likely resided here, some being chained behind strong doors.

Founding and Early Years

Much credit has been given to Jeremiah Yellott, a mariner and prosperous merchant, for promoting the cause of a permanent hospital at this site, but it is likely a historical embellishment. Influential families more likely banded together and petitioned the State to charter such an institution. Some private citizens understood the need for such a general hospital, pledging money for its support. What is certain is that the Maryland legislature considered a bill to grant a charter to found such an institution in November of 1797. In the Senate proceedings of early 1798, after the passage of the bill of incorporation, the legislators redirected $8,000 originally earmarked for an educational academy to the cause of the hospital, since “this institution is an object of great state importance, and extensively interesting to the people of Maryland.”

Much credit has been given to Jeremiah Yellott, a mariner and prosperous merchant, for promoting the cause of a permanent hospital at this site, but it is likely a historical embellishment. Influential families more likely banded together and petitioned the State to charter such an institution. Some private citizens understood the need for such a general hospital, pledging money for its support. What is certain is that the Maryland legislature considered a bill to grant a charter to found such an institution in November of 1797. In the Senate proceedings of early 1798, after the passage of the bill of incorporation, the legislators redirected $8,000 originally earmarked for an educational academy to the cause of the hospital, since “this institution is an object of great state importance, and extensively interesting to the people of Maryland.”

The interest of the State or its people, however, would not be sustained. By 1801, when the first ward opened in the partially completed Hospital at Baltimore, its noble purpose had been subverted. During its early years, the institution appears to have catered largely to sick sailors under a U.S. Government contact. From 1802 to mid-1807, the hospital served primarily as a marine hospital, seemingly forgetting its mission to the poor and mentally ill. Instead, another newly founded institution, the Baltimore Dispensary, served as the city’s charity hospital, caring for over 600 patients in 1801 alone.

Since few hospital records for this period exist, it is impossible to determine the number of patients under care. While it is not known for certain if the mentally ill were confined in the institution during this time, some evidence exists to throw doubt upon this supposition. In 1807, Baltimore Mayor Thorowgood Smith would note: “Our City Hospital, if ever designed as a receptacle of deranged persons (and it would appear that this was one object intended to be accomplished by those who caused it to be erected), is very badly constructed for the purpose and should… maniacs under certain terms and conditions…be admitted there, appropriations will be required to make the indispensable alterations in the building.”

Evidentially the operation proved less than economically viable. The 1804 report of the Visiting Committee regarded the building to be in poor shape, noting decaying fences, unpainted exterior woodwork, and windows lacking weights or fastenings with the propensity to crash down and shatter. In July 1807, after the Hospital lost the U.S. government contract, only two patients resided within the facility. The city refused to sign a long-term contract with the resident physician, who supplemented his income by growing crops of vegetables on the hospital grounds.

In 1808, community leaders and other Baltimoreans once again resurrected the prospect of the Hospital at Baltimore as a care center for the mentally ill. Mayor Smith, in his message of that year, states: “An effort has been made by you…and myself acting in our capacity as citizens of Baltimore, together with the members of the [city] Board of Health, a number of the Clergy, Physicians and other citizens to obtain from the Legislature of Maryland funds for the support of indigent lunatics within the State for this Hospital. This application has not been successful.”

The year 1808, however, appeared to be a pivotal one in the fortunes of the institution as the treatment of the mentally ill became a stated goal. The lease of the hospital to two entrepreneurial physicians, Drs. Colin Mackenzie and James Smyth, may have enhanced the reputation of the facility and prompted citizens to send their family members to Baltimore. Mackenzie had been trained at the prestigious Pennsylvania Hospital, the nation’s pioneering mental healthcare institution.

Several Chancery Court cases from after 1810 included documentation attesting to mentally ill patients being treated at the hospital. The cost for a patient’s care was about $100 a year, a considerable sum for that time, plus incidentals. Patients with destructive tendencies had to reimburse the facility for their actions.

Though admittance was governed by the ability to pay, certain cases were underwritten by charities or the city. In 1813, three Baltimoreans petitioned the city regarding a “female maniac” who had been found on the street with her near-dead infant clutched within her arms. Both were admitted to the hospital, with their bills paid by charity. The infant died, but the mother recovered slowly, and the petitioners hoped the city could take over the expenses as the charitable funds had run out. The city replied that they could not; the woman should instead be sent to the city-run almshouse.

Evidence suggests that the hospital made an effort to retain patients where the ability to pay still existed. In 1817, the hospital steward petitioned the court for the guardianship over an elderly dementia patient still possessing an estate. The petition was successful and the woman remained under medical care.

The Hospital at Baltimore, however, acted mostly as a general hospital. A patient census for 1819-20 indicates no more than 13 percent of the cases being those relating to mental illness. Unfortunately, no documentary evidence exists to suggest overall treatment or level of care for patients until 1834 when, due to economic circumstances, the State assumed the management of the facility.

Digital images from the Maryland State Archives:

Charles Varle. Warner & Hanna’s Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore [detail], 1801 , MSA SC 1213

E. Sachse & Co., E. Sachse & Co. Bird’s Eye View of the City of Baltimore [detail],1869, MSA SC 3132

Charles Varle. Warner & Hanna’s Plan of the City and Environs of Baltimore [detail], 1801 , MSA SC 1213

E. Sachse & Co., E. Sachse & Co. Bird’s Eye View of the City of Baltimore [detail],1869, MSA SC 3132

No comments:

Post a Comment